From early childhood we have been learning about the Ancient Silk Route, however the idea of a Silk Road was completely unknown in ancient times, not a single ancient record, either Chinese or western, refers to its existence. Instead, it was invented as late as 1877 by a Prussian geographer, “Baron voi Richthofen”, who, while engaged in a geological survey of China, was charged with dreaming up a route for a railway linking Berlin with Beijing with a view to establishing German colonies and infrastructure projects in the region. This route he named die Seidenstraßen which in translate as ‘the Silk Roads’ – the first use of the term.

From early childhood we have been learning about the Ancient Silk Route, however the idea of a Silk Road was completely unknown in ancient times, not a single ancient record, either Chinese or western, refers to its existence. Instead, it was invented as late as 1877 by a Prussian geographer, “Baron voi Richthofen”, who, while engaged in a geological survey of China, was charged with dreaming up a route for a railway linking Berlin with Beijing with a view to establishing German colonies and infrastructure projects in the region. This route he named die Seidenstraßen which in translate as ‘the Silk Roads’ – the first use of the term.

It was not until the year 1938 that the term Silk Road appeared in English, as the title of a popular book by a Swedish explorer, Sven Hedin. Since then, the term has captured the global imagination and the ‘reopening of the Silk Road has been announced by President Xi Jinping of China as part of his Belt and Road Initiative. In this way, the idea has been effectively co-opted and actively mobilised as part of Chinese foreign Policy, partly to obfuscate its economic and military projections of power. It has now been elevated to unquestioned fact.”

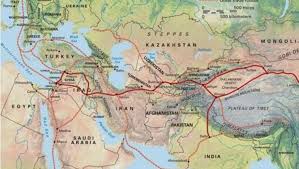

Following Richthofen, maps of the overland Silk Route linking east and west, the Mediterranean with the South China Sea, often feature a single small arrow pointing south from Kashgar down towards the Himalayas. That arrow is labelled: ‘To India’. The real economic action, the map implies, took place between China and western Europe; India was an almost passive observer of, and a lucky recipient of largesse from, the main highway of intercontinental commerce running far to its north.

The reality is very different. Although overland trade routes through Iran were clearly of central importance when Mughal rule stretched from the Mediterranean to the South China Sea during the 13 century, this was not the case during the classical and early medieval era. Indeed the Roman Empire and China actually had only the haziest notions of each other’s existence – vaguely aware of each other, but almost never in direct contact.

In reality, goods from China largely reached Rome merely as an exotic supplement to its thriving commerce with India, and passed through ancient Indian ports.

From the time of Augustus ( 31 BCE-14 CE), for several centuries, Rome and ancient India were major trading partners, with hundreds of huge cargo ships passing directly between the two each year. Roman trading manuals reveal a real, practical familiarity, even intimacy, with the ports of India, especially those on the west coast, with detailed descriptions that clearly derive from first-hand experience and direct observation. If China and Rome ever came face to face, they did so here in the quays, ports and bazaars of coastal India.

In contrast, the Silk Route barely existed in antiquity. For while good certainly passed backwards and forwards as part of local or regional trade, with some objects eventually moving long distances, there was never, at any point in history, any one east-west overland trade route linking the China Sea with the Mediterranean. Nor was there any free movement of goods between China and the west at any point before the Mughal period in the 13 century.

Even Marco Polo, the man now most closely associated with the Silk Road, never once mentions the term, though it was during his lifetime that travel became easiest through the borderless enormity of the vast Mughal Empire.

Even silk, the most celebrated Chinese export, arrived in Roman lands only indirectly, usually by boat, via India, where much of the silk that reached the west was actually manufactured.

Moreover, Silk was never the main commodity imported to the west from the east.

Additionally, on excavation in China, there were found a handful of Roman Coins, which indicates the absence of any steadfast trade activity.

Munaza Kazmi holds MPhil in Management Sciences, is a travel writer, an author, and a co-author of scientific contributions in national and international publications.