“«Since when you have taken people for slaves and they were born free»”

Umar bin al-Khattab, the Second Khalifa of the Muslims

By: Naveed Ahmad Khan

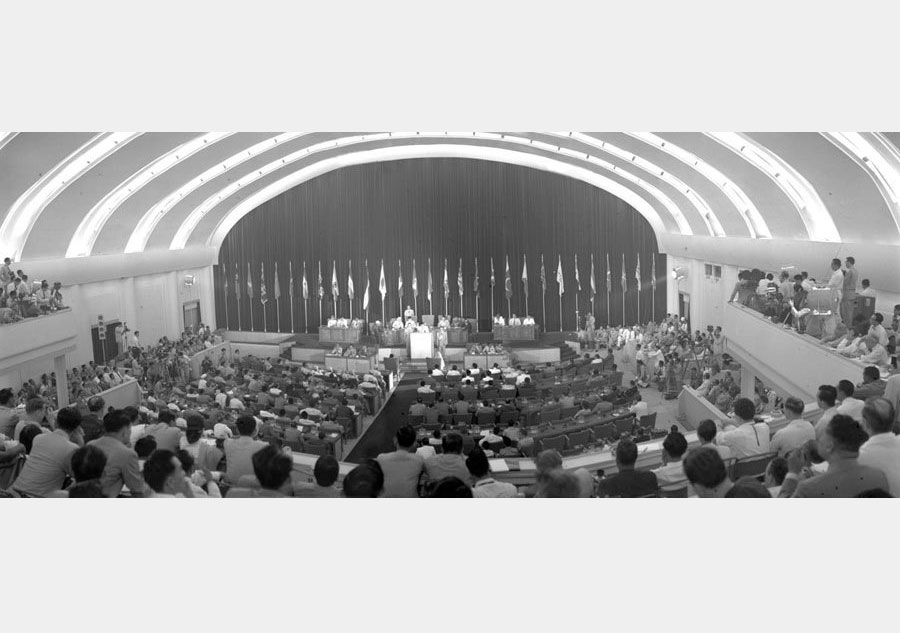

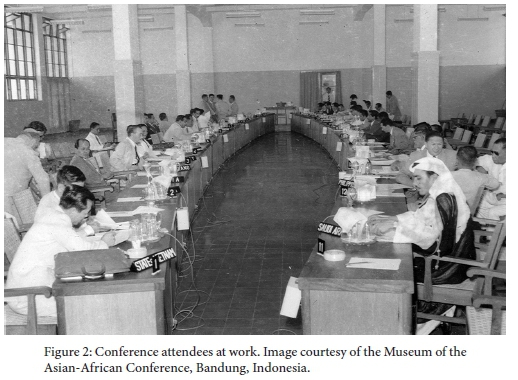

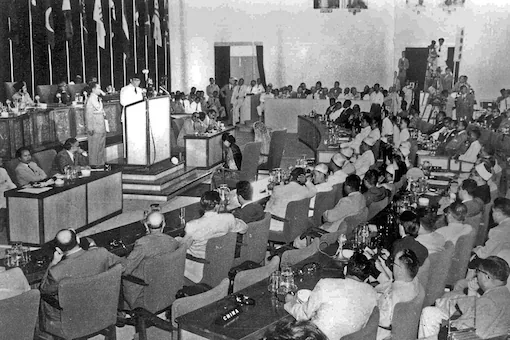

From April 18 to April 24, 1955, delegates from twenty-nine countries in Asia-Africa convened in Bandung, Indonesia, to discuss the common challenges their nations faced in navigating a postcolonial world. The Asian–African Conference, popularly known as the Bandung Conference, was a sensation around the world. Never before had leaders from so many non-Western countries gathered together to make common cause. But the Conference’s iconic status, coupled with a growing global sense of nostalgia for the supposedly optimistic days of the 1950s, means that many legends that have subsequently sprung up about the event are simply not true. Seldom has historical memory distorted and misrepresented any single event in quite so many different ways. Accordingly, it is valuable to include an extended discussion of the facts surrounding the Bandung Conference: how it was organized, who participated, what was said, and—perhaps most important—what was not said.

The Asian–African Conference was the brainchild of Indonesian Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo, who planned the proceedings in collaboration with the prime ministers of Burma, Ceylon, India, and Pakistan. These five men met in Bogor, Indonesia, in December 1954 to draft the Conference’s agenda and to issue invitations.

The Asian–African Conference was the brainchild of Indonesian Prime Minister Ali Sastroamidjojo, who planned the proceedings in collaboration with the prime ministers of Burma, Ceylon, India, and Pakistan. These five men met in Bogor, Indonesia, in December 1954 to draft the Conference’s agenda and to issue invitations.

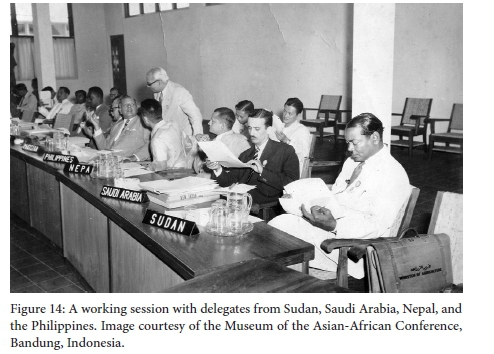

After considerable debate, the five hosts agreed to send invitations to twenty-five countries. From the continent of Africa, they invited four of the five independent countries of the day: Egypt, Ethiopia, Liberia, and Libya. They declined to invite the fifth, South Africa, whose policy of apartheid was criticized in the Conference’s final communiqué. In addition to the four independent African countries, the conveners extended invitations to the Gold Coast (modern-day Ghana), Sudan (then under joint British–Egyptian control), and the Central African Federation (modern-day Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe). The Central African Federation was the only invited country that did not agree to send a representative to Bandung.

Delegations from twenty-nine countries convened in Bandung on April 18, 1955, a date that Indonesian President Sukarno celebrated in his welcoming address as the anniversary of the beginning of the American Revolution. Sukarno praised the American War of Independence as “the first successful anti-colonial war in history” and quoted from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.”

Delegations from twenty-nine countries convened in Bandung on April 18, 1955, a date that Indonesian President Sukarno celebrated in his welcoming address as the anniversary of the beginning of the American Revolution. Sukarno praised the American War of Independence as “the first successful anti-colonial war in history” and quoted from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere.”

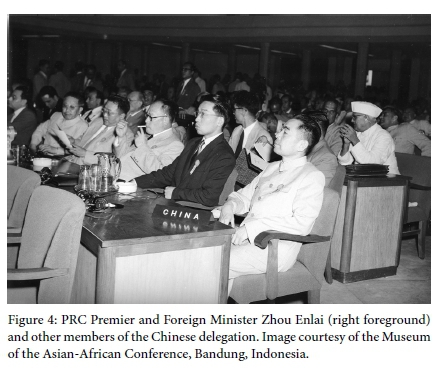

Among the most prominent world leaders who attended the Conference were Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Burmese Prime Minister U Nu, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Chinese Premier and Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai. Most other countries sent high-ranking representatives, but not their heads of government. Nasser and Zhou attracted particular attention as newcomers to the international scene. The Bandung Conference was only Nasser’s second foreign trip since leading the 1952 Free Officers’ Revolution: his previous trip was a pilgrimage to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. For most of the delegates in attendance, the Bandung Conference was also the first time they had engaged with any representative of Communist China. Nehru, his daughter Indira Gandhi, U Nu, Nasser, and Zhou spent a considerable amount of social time with one another at the Conference.

In addition to the participating delegations, a variety of individuals from around the world came to observe the Conference in an unofficial capacity. These observers included two notable African Americans. One was the author Richard Wright, whose book The Color Curtain described his experiences in Bandung. Wright felt a connection between his identity as an African American and the identities of the non-Western leaders gathered in Bandung, whom he described as “the despised, the insulted, the hurt, the dispossessed—in short, the underdogs of the human race.” The other important African American to attend the Conference was Adam Clayton Powell, a Democratic congressman from New York whose district included Harlem. Powell was the only member of the American government to attend the Conference, which he did despite the objections of American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.

In addition to the participating delegations, a variety of individuals from around the world came to observe the Conference in an unofficial capacity. These observers included two notable African Americans. One was the author Richard Wright, whose book The Color Curtain described his experiences in Bandung. Wright felt a connection between his identity as an African American and the identities of the non-Western leaders gathered in Bandung, whom he described as “the despised, the insulted, the hurt, the dispossessed—in short, the underdogs of the human race.” The other important African American to attend the Conference was Adam Clayton Powell, a Democratic congressman from New York whose district included Harlem. Powell was the only member of the American government to attend the Conference, which he did despite the objections of American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.

Dulles opposed the convening of the Asian–African Conference on the grounds that it would offer a forum for Communist countries to criticize the West. He also worried that attendees at the Conference would condemn American- and British-led military alliances such as SEATO and CENTO. The British and French governments were especially concerned about the effect the Conference would have on their own colonies in Africa. The British government actively discouraged the Gold Coast and the Central African Federation from sending representatives to the Conference. The French ambassador in Washington asked Dulles to use his influence to convince the governments of Liberia and Ethiopia to decline their invitations as well, but Dulles refused to do so. Instead, he asserted that it would be best if pro-Western countries sent “the ablest possible representation” in order to articulate the anti-Communist position. Dulles specifically singled out Lebanon’s delegate, the Harvard-educated Charles Malik, as the kind of participant he hoped would attend the Conference.

Dulles opposed the convening of the Asian–African Conference on the grounds that it would offer a forum for Communist countries to criticize the West. He also worried that attendees at the Conference would condemn American- and British-led military alliances such as SEATO and CENTO. The British and French governments were especially concerned about the effect the Conference would have on their own colonies in Africa. The British government actively discouraged the Gold Coast and the Central African Federation from sending representatives to the Conference. The French ambassador in Washington asked Dulles to use his influence to convince the governments of Liberia and Ethiopia to decline their invitations as well, but Dulles refused to do so. Instead, he asserted that it would be best if pro-Western countries sent “the ablest possible representation” in order to articulate the anti-Communist position. Dulles specifically singled out Lebanon’s delegate, the Harvard-educated Charles Malik, as the kind of participant he hoped would attend the Conference.

The Asian–African Conference is often misrepresented as the beginning of the “Non-Aligned Movement” of countries that sought to take a neutral position in the Cold War. While a few Conference attendees, led by Nehru, had begun by 1955 to advance a “neutralist” ideology, the reality was that the majority of countries in attendance in Bandung were explicitly aligned with the United States. During the Conference’s plenary session, representatives of Iran, Iraq, the Philippines, Turkey, Cambodia, and Thailand all criticized the Soviet Union, with some delegates asserting that Soviet ambitions in Eastern Europe were tantamount to colonialism. This discussion forced Zhou Enlai to speak in defense of the Communist bloc. Since the organizers of the Conference prioritized consensus, they produced a final communiqué that said nothing about the ongoing Cold War.

The Asian–African Conference is often misrepresented as the beginning of the “Non-Aligned Movement” of countries that sought to take a neutral position in the Cold War. While a few Conference attendees, led by Nehru, had begun by 1955 to advance a “neutralist” ideology, the reality was that the majority of countries in attendance in Bandung were explicitly aligned with the United States. During the Conference’s plenary session, representatives of Iran, Iraq, the Philippines, Turkey, Cambodia, and Thailand all criticized the Soviet Union, with some delegates asserting that Soviet ambitions in Eastern Europe were tantamount to colonialism. This discussion forced Zhou Enlai to speak in defense of the Communist bloc. Since the organizers of the Conference prioritized consensus, they produced a final communiqué that said nothing about the ongoing Cold War.

Because the final communiqué had to be palatable to the governments of twenty-nine countries, it was for the most part a fairly general document. It committed the signatories to cooperate to promote economic development in the region, including by exchanging technical assistance, but it specifically allowed them to continue accepting aid from governments outside the region, by which it meant the United States and the Soviet Union. It condemned “colonialism in all its manifestations” as “an evil which should speedily be brought to an end,” but it called explicitly for the independence of only three colonies: Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. The communiqué also condemned racial discrimination and singled out South Africa as a country in which racism needed to be “eradicated.” Finally, the communiqué asserted that the countries of Asia and Africa could promote world peace and called for “universal disarmament.”

Because the final communiqué had to be palatable to the governments of twenty-nine countries, it was for the most part a fairly general document. It committed the signatories to cooperate to promote economic development in the region, including by exchanging technical assistance, but it specifically allowed them to continue accepting aid from governments outside the region, by which it meant the United States and the Soviet Union. It condemned “colonialism in all its manifestations” as “an evil which should speedily be brought to an end,” but it called explicitly for the independence of only three colonies: Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. The communiqué also condemned racial discrimination and singled out South Africa as a country in which racism needed to be “eradicated.” Finally, the communiqué asserted that the countries of Asia and Africa could promote world peace and called for “universal disarmament.”

While the Asian–African Conference did not itself signal the beginning of the Non-Aligned Movement, it did provide a setting in which several relationships that later helped launch that movement could be formed. In particular, Nehru and Nasser met for the first time in New Delhi en route to the Conference. When the Non-Aligned Movement was established in 1961 at the Belgrade Conference in Yugoslavia, Nehru and Nasser—along with several non-Asian, non-African leaders such as Josip Broz Tito—were among its most vocal proponents.

The delegates at the Asian–African Conference did not establish any kind of permanent organization directly as a result of the Conference, but it did mark the beginning of a period of intense interest in promoting cooperation among Asian and African countries. In December 1957, another conference in Cairo founded the Asian–African People’s Solidarity Organization, which, unlike the Asian–African Conference, included the participation of the Soviet Union. The first president of an independent Algeria, Ahmed Ben Bella, planned to host a second Asian–African Conference in Algiers in 1965, but those plans were scuttled in part because of the coup that overthrew Ben Bella in June of that year and in part because of Chinese opposition to allowing the Soviet Union to attend.

Today, the Asian–African Conference is often mythologized, especially by the current governments of participating countries, as an example of a spirit of cooperation among Third World countries that has since been lost. This impulse toward nostalgia often leads to the spread of incorrect information about the Conference. American scholar Robert Vitalis has catalogued erroneous reports, sometimes from official government publications, about the attendance in Bandung of various anticolonial leaders who were not in fact there, including Tito, Kwame Nkrumah, Fidel Castro, and Jomo Kenyatta.

Despite this confusion, the Asian–African Conference must be recognized as an event that encouraged many leaders of developing countries to articulate a vision of global anti-imperialist cooperation beyond their own borders. The Conference was also a trigger for some governments, including those of China, Egypt, and Ghana, to begin to seek both domestic and international legitimacy by portraying themselves as exemplars of a commitment to Third World solidarity.

Sukarno’s Opening Speech

Sukarno’s Opening Speech

In his opening speech at the first Asian-African Conference, President Sukarno of Indonesia recognized that the gathering of the leaders of the 29 Asian-African independent countries was a result of the sacrifices made by their forefathers and by the people of their own and younger generations. “The hall was filled not only by the leaders of the nations of Asia and Africa but also contained within its walls the undying, the indomitable, the invincible spirit of those who went before them”, he said. Their struggle and sacrifice paved the way for this meeting of the highest representatives of independent and sovereign nations from two of the biggest continents of the globe. In a historic event, Asian and African peoples were meeting together to discuss and deliberate upon matters of common concern to them.

Sukarno stated that the burden of the delegates attending the Conference was not a light one. “For many generations our peoples have been the voiceless ones in the world. We have been the unregarded, the peoples for whom decisions were made by others whose interests were paramount, the peoples who lived in poverty and humiliation. Then our nations demanded, nay fought for independence, and achieved independence, and with that independence came responsibility. We have heavy responsibilities to ourselves, and to the world, and to the yet unborn generations. But we do not regret them”.

Below are some extracts of his speech:

“We are often told ‘Colonialism is dead’. Let us not be deceived or even soothed by that. I say to you, colonialism is not yet dead. How can we say it is dead, so long as vast areas of Asia and Africa are unfree. And, I beg of you do not think of colonialism only in the classic form which we of Indonesia, and our brothers in different parts of Asia and Africa, knew. Colonialism has also its modern dress, in the form of economic control, intellectual control, actual physical control by a small but alien community within a nation. It is a skilful and determined enemy, and it appears in many guises. It does not give up its loot easily. Wherever, whenever and however it appears, colonialism is an evil thing, and one which must be eradicated from the earth.

“If this Conference succeeds in making the peoples of the East whose representatives are gathered here understand each other a little more, appreciate each other a little more, sympathise with each other’s problems a little more – if those things happen, then this Conference, of course, will have been worthwhile, whatever else it may achieve. But I hope that this Conference will give more than understanding only and goodwill only – I hope that it will falsify and give the lie to the saying of one diplomat from far abroad: “We will turn this Asian-African Conference into an afternoon-tea meeting”.

“I hope that it will give evidence of the fact that we Asian and African leaders understand that Asia and Africa can prosper only when they are united, and that even the safety of the World at large cannot be safeguarded without a united Asia-Africa. I hope that this Conference will give guidance to mankind, will point out to mankind the way which it must take to attain safety and peace. I hope that it will give evidence that Asia and Africa have been reborn, nay, that a New Asia and a New Africa have been born!

“Our task is first to seek an understanding of each other, and out of that understanding will come a greater appreciation of each other, and out of that appreciation will come collective action. Bear in mind the words of one of Asia’s greatest sons: “To speak is easy. To act is hard. To understand is hardest. Once one understands, action is easy”. Let us remember that the highest purpose of man is the liberation of man from his bonds of fear, his bonds of human degradation, his bonds of poverty – the liberation of man from the physical, spiritual and intellectual bonds which have for too long stunted the development of humanity’s majority.”

The other 28 leaders also spoke eloquently in calling for unity among Asian and African countries and for greater solidarity, self-determination, mutual respect for sovereignty, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, and equality.

The Bandung final declarations

The Final declarations of the 1955 Bandung Asian-African Conference provided the basis for South-South cooperation with concrete proposals for promoting economic, political, technological, cultural spheres. It declared full support of the fundamental principles of human rights as set forth in the Charter of the United Nations and took note of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations in a moment in history when many South nations were still under Western colonial rule.

The communiqué deplored all forms of racial segregation and discrimination. In declaring support for the cause of freedom and independence for all peoples it also deplored colonialism, in all its manifestations.

The communiqué took note that several States had still not been admitted to the United Nations, and that for effective cooperation and world peace, membership in the United Nations should be universal. The leaders also considered that representation of Asian and African countries in the UN Security Council, in relation to the principle of equitable and geographical distribution, was inadequate, as it is today. The right to self-determination, stated the communiqué, should be enjoyed by all peoples.

The Ten Bandung Principles enunciated in 1955 continue to be as relevant today as it was 60 years ago and in the decades since. These are as follows:

“Free from mistrust and fear, and with confidence and goodwill towards each other, nations should practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbours and develop friendly cooperation on the basis of the following principles:

“1. Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

“2. Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations.

“3. Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations large and small.

“4. Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country.

“5. Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself singly or collectively, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

“6. (a) Abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defense to serve the particular interests of any of the big powers,

(b) Abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries.

“7. Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country.

“8. Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, such as negotiation, conciliation, arbitration or judicial settlement as well as other peaceful means of the parties’ own choice, in conformity with the Charter of the United Nations.

“9. Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation.

“10. Respect for justice and international obligation.”

The 1955 Bandung communiqué concluded by expressing its conviction that friendly cooperation in accordance with the 10 Principles of Bandung would effectively contribute to the maintenance and promotion of international peace and security, while cooperation in the economic, social and cultural fields would help bring about the common prosperity and well-being of all.

In the six decades after the 1955 Bandung Conference that gave rise to the “Bandung Spirit” of South-South cooperation, decolonization has for the most part taken place, with most developing countries now independent. The basic principles of Bandung, namely, mutual interest, solidarity and respect for national sovereignty, continue to play important roles in shaping and guiding the relations of developing countries with each other. Developing countries have also joined the United Nations and actively developed different regional and multilateral South-South institutions to defend and promote their common interests in the various multilateral negotiating processes. The “Bandung Spirit” continues to animate and motivate the spirit of South-South cooperation and Indonesia did it. This Asia Africa Bandung conference final declaration in 1955 but which still waiting for implementation