University of London Unveils Pakistan Law Microcredential at Islamabad Ceremony

Spokesman Report

Islamabad December 01, 2025: University of London Dean Patricia Mckeller and Saad Wasim Launches Introductory Microcredential on Pakistan Law within their Undergraduate Laws Degree!

The University of London launched yesterday the Micro Credential on Introduction to Pakistan Law in Islamabad. The event was attended by the Federal Minister for Information and Broadcasting Attaullah Tarar and Minister of State for Law & Justice Barrister Aqeel Malik as the Chief Guests.

Dr. Faisal Mushtaq, Chairman & CEO TMUC Higher Education Group and The Millennium Education attended as the Guest of Honour. Other key stakeholders attended the event, including prominent lawyers and employers, esteemed alumni, regulators, partners and our wonderful RTC Heads.

All the attendees highly appreciated this initiative from UG Laws and felt this would further strengthen the University of London UG Laws programme in Pakistan!

Special thanks to Dean UG Laws, Patricia Mckeller and Saad Wasim, Regional Advisor South Asia for University of London for turning this dream into reality!

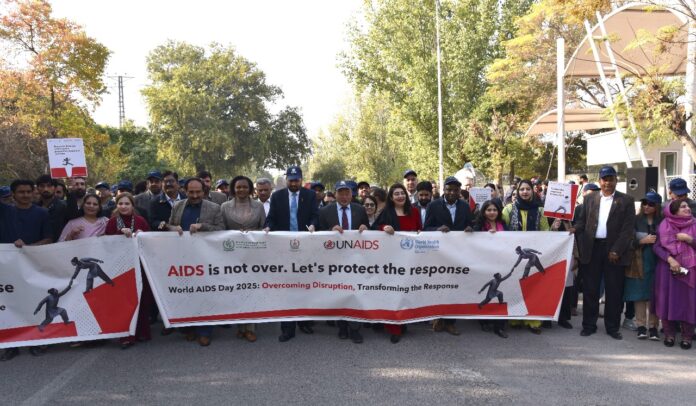

HIV infections rise in Pakistan; WHO and UNAIDS call to action

Spokesman Report

1 December 2025, Islamabad, Pakistan – On the occasion of World AIDS Day, the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNAIDS are calling for action to reverse a trend that has made Pakistan home to one of the fastest-growing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemics in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, with new infections rising by 200% over the last 15 years – from 16,000 in 2010 to 48,000 in 2024.

While HIV predominantly affected high-risk groups in the past, it is now spreading to children, spouses and the wider community due to unsafe blood management and injection practices, gaps in infection prevention and control, a lack of HIV testing during antenatal care, unprotected sexual activity, stigma and limited access to HIV services.

Under the theme “Overcoming disruption, transforming the AIDS response”, WHO and UNAIDS joined forces with Pakistan’s Ministry of Health to mark the date with an awareness walk calling for collective and individual action to intensify the HIV response and preventive measures. The main goal: to end the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) – which applies to the most advanced stages of HIV infection – as a public health threat by 2030.

“The discrimination, the stigma, and this disease cannot be curtailed only by us. It has to be the communities; it has to be the health regulatory authorities… We need everyone involved to end unsafe practices for injections and blood transfusions. We need to educate people. We need to take our clinicians on board as well. All of us, together, can achieve our goals. We need to give the children and the adults of Pakistan the healthy future they deserve, which is HIV-free,” said Pakistan’s Health Director General Dr Ayesha Majeed Isani.

It is estimated that 350,000 people are living with HIV in Pakistan, but almost 8 in 10 persons affected do not know their status. Children are increasingly affected, with new cases among those aged 0-14 years surging from 530 cases in 2010 to 1,800 in 2023.

Over the last decade, Pakistan has increased eightfold the number of persons living with HIV who receive antiretroviral therapy (ART) – from around 6,500 in 2013 to 55,500 in 2024 – thanks to joint efforts by the Government, UN entities, and partners. The country has also increased the number of antiretroviral therapy centres from 13 in 2010 to 95 in 2025.

Despite progress, in 2024, in Pakistan only an estimated 21% of people living with HIV knew their status, 16% of them were on treatment, and 7% had achieved viral load suppression. Over 1,100 AIDS-related deaths were reported in 2024.

“The surge in new cases and recent outbreaks that have particularly affected children – jeopardizing their future and Pakistan’s future – are a stark reminder of the urgent need to intensify joint efforts and mobilize both international and domestic resources to end the public threat of AIDS for good. WHO will stand with Pakistan and partners to protect the present and future generations from HIV, leaving no one behind,” said WHO Representative in Pakistan Dr Luo Dapeng.

“Together, we can still end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030, if we act with urgency, unity, and renewed commitment. Countries must make radical shifts to HIV programming and funding. The global HIV response cannot rely on domestic resources alone. The international community must renew its commitment to ending AIDS by 2030 and come together to bridge the financing gap to expand prevention, testing, treatment, and care, particularly for key populations, women and children”, said UNAIDS Director in Pakistan, Trouble Chikoko.

In Pakistan, children have been tragically exposed to HIV through unsafe injections and blood transfusions in recent outbreaks in Shaheed and Benazirabad, Hyderabad, Naushahro Feroze, and Pathan Colony (2025), Taunsa (2024), Mirpur Khas (2024), Jacobabad and Shikarpur (2023), and Larkana (2019). In several of these outbreaks, over 80% of detected cases involved children.

Only 14% of pregnant women in need of treatment receive it to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, leaving thousands of children at risk. Among children aged 0–14 living with HIV, only 38% are on treatment.

WHO and UNAIDS stand with Pakistan and partners to end AIDS as a public health threat and build a healthier future for all.

Al-Shifa expands free care but cataract-related economic losses grow.

Spokesman Report

RAWALPINDI (Dec 01):Pakistan’s cataract burden continues to rise despite an expansion in treatment facilities, driven by the fast-growing diabetes epidemic, an ageing population, malnutrition, ultraviolet exposure and late diagnosis. Prof Dr Sabihuddin Ahmed, Head of the Cataract Department at Al Shifa Trust Eye Hospital, said these pressures are outpacing the system’s ability to deliver timely care, especially in areas with limited specialist coverage. He said closing the treatment gap requires a shift toward decentralized services, including mandatory screening for diabetic patients and integrating basic eye exams into primary healthcare networks.

He said doctors under the Al Shifa network carry out about 8500 free cataract surgeries every month across six hospitals. This expansion is donor-supported but remains insufficient as diabetes driven cataract rises. Pakistan ranks first globally in diabetes prevalence with 34.5 million adults suffering from the disease, which could reach 70.2 million by 2050. Provincial prevalence stands at 16 percent in Punjab, 15 percent in Baluchistan, 14 percent in Sindh, and 11 percent in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. About 230000 Pakistanis die annually due to diabetes related complications.

Talking to the media, Prof Ahmed said the cataract surgical rate is now more than double the 2002 level, yet millions remain untreated. There are about 570000 adults blind from cataract and 3.56 million with visual issues. Meeting needs by 2030 will require at least 1.84 million surgeries annually. He said economic losses are widening because untreated cataract reduces labour participation, lowers household productivity, and increases dependency among older earners. WHO estimates show global productivity losses of 411 billion dollars from vision impairment. IN Pakistan, the private sector performs 42.4 percent of surgeries, NGOs 39.9 percent, and the public sector 17.7 percent, keeping most of the burden on non-state providers.

Pakistan has only 15 ophthalmologists per million population, far fewer than in developed countries. Many districts have none, and most specialists are urban-based, limiting rural access. He said women face mobility barriers, fewer financial resources, and delayed hospital visits, resulting in higher untreated cataracts. Private surgery costs remain a major barrier, while public hospitals struggle with outdated equipment and long queues. He said provincial health systems should adopt routine diabetes screening, embed eye care in basic health units, and expand training to prevent avoidable blindness.

A Lone Gunman Sparks Trump’s War on Legal Immigrants

On a gray November afternoon, just two blocks from the White House, the story Donald Trump wanted to tell about a “safe and peaceful” capital exploded in a hail of bullets. Two members of the National Guard, Specialist Sarah Beckstrom and Staff Sergeant Andrew Wolfe, were on routine foot patrol when an Afghan-born gunman walked up and opened fire in a sudden ambush that stunned the entire nation. The attack was quick, brutal, and merciless. Beckstrom died the next day, and Wolfe continues to fight for his life. It was an attack that pierced the heart of the security narrative Trump had been promoting, especially after deploying more than two thousand National Guard troops across Washington, D.C., in a show of restored order.

The shock to the system was immediate. Television screens filled with images of uniformed soldiers bleeding on downtown sidewalks in full view of the White House. What was meant to be proof of law and order became a terrifying reminder that chaos needs only one crack to break through. Very quickly, the identity of the attacker transformed the discussion from crime prevention to national identity.

The shooter, Rahmanullah Lakanwal, had entered the United States legally under Operation Allies Welcome after the fall of Kabul. He had been part of a U.S.-backed Afghan unit, passed multiple layers of vetting, and was given asylum earlier this year. Those facts did not matter in the political storm that followed.

Trump condemned the attack as an act of “pure evil” and moved instantly from grief to policymaking. His anger, already directed at illegal immigration, now expanded to encompass legal immigrants from what he calls “Third World countries.” He demanded a halt to asylum approvals, reviews of thousands of past green-card cases, and a wider freeze on visas from dozens of nations. A single criminal suddenly became the symbol of an entire global population.

For Afghan evacuees, the consequences are direct and devastating. Tens of thousands remain in legal limbo in Pakistan, the Gulf, and elsewhere, waiting for visas. Many served U.S. forces, risked their lives, and were promised safety. Now, because of one man’s descent into violence, their futures are frozen. Trump’s new directives also cast a long shadow over immigrants worldwide, including those who spent decades waiting for lawful entry. Families who followed every rule, gathered every document, passed every interview, and waited patiently for their priority dates now see their dreams threatened overnight.

My own family is among those who waited almost twenty years for a lawful, transparent immigration process. We began in 2007, sponsored by an American relative, and endured delays, repeated paperwork, bureaucratic hurdles, and shifting immigration quotas. Only in 2024 did we finally arrive as legal permanent residents. Our journey reflects the commitment millions make to follow the rules, respect the system, and contribute to American society. And yet today, even people like us — legal, vetted, documented — find ourselves under the shadow of suspicion because of one man’s crime.

Security failures deserve investigation. Policies deserve review. But collective punishment is neither justice nor strategy. The attacker passed multiple layers of security screening, worked alongside U.S. agencies, and seemed to deteriorate quietly while navigating a life of legal uncertainty and psychological distress in a new country. His actions were his own. To transform that into a blanket indictment of millions is a political choice, not a security necessity.

This instinct toward collective punishment has shaped some of the darkest moments of modern history. After 9/11, the United States invaded Afghanistan and Iraq, killing hundreds of thousands, displacing millions, and reducing entire societies to rubble, even though the attacks were carried out by nineteen individuals. In Libya, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, entire populations paid for crimes they did not commit.

On 7 October, Hamas militants carried out a brutal attack that killed Israelis. Instead of targeting only the perpetrators, the retaliation turned into the collective punishment of an entire civilian population in Gaza. More than seventy thousand people were killed. Seventy percent of Gaza’s residents became homeless, and many now face death from winter cold, hunger, and exposure. Instead of punishing those who committed the crime, an entire people paid the price. This same principle — punishing the innocent for the actions of the guilty — is now echoing across America’s immigration debate. Interestingly, human rights often vanish the moment U.S. strategic interests are invoked, and the victims are left with the consequences.

Trump’s anger is understandable on a human level. A young woman in uniform is dead. Another soldier may still die. His promise of security has been shattered in the most public and humiliating way possible. But leadership is not defined by anger; it is defined by what anger is allowed to unleash. Justice demands that the killers and any accomplices be punished fully and swiftly. It does not demand that millions of unrelated immigrants — in Kabul, Karachi, Nairobi, or Washington — be treated as guilty by association.

If America now shuts its doors to lawful immigrants, rescinds visas, freezes green-card approvals, and destroys the hopes of families who followed every law, it will not be making itself safer. It will be abandoning the principles that once distinguished its moral claim to leadership. The United States has always been strongest when it recognized the difference between a criminal and a community. That line is now dangerously close to being erased.

It is, of course, the duty of any government to protect its citizens and to learn from failures. The public has a right to know whether Operation Allies Welcome missed warning signs in Lakanwal’s background, or whether mental-health problems went unaddressed. But the emerging picture is not one of negligence; it is of a man who passed extensive biometric, biographic, and intelligence checks, worked with U.S. agencies, and then unraveled in the shadows of a new life.

In the coming weeks, investigators will uncover more about the gunman’s motives, background, and state of mind. Politicians will shout, the public will divide, and courts will be asked to intervene. But underneath all of this lies a single question that tests the values of the nation: Will America punish the guilty — or the innocent? One path leads to justice. The other leads to fear, prejudice, and betrayal of the very ideals engraved on the Statue of Liberty.

For the sake of the young soldiers who bled on the streets of Washington, and for the millions who still believe in the promise of America, one can only hope that reason, not rage, finally prevails.

The writer is Press Secretary to the President (Rtd),Former Press Minister, Embassy of Pakistan to France,Former Press Attaché to Malaysia and Former MD, SRBC.He is living in Macomb, Michigan, USA.

Kabul’s Manufactured Airstrike Allegations: A Forensic Look at a Narrative Built on Evasion

The latest accusation from Kabul—that Pakistan conducted an airstrike on a supposed civilian home in the Khost–Bermal region—arrived not with evidence, not with coordinates, not with victim identities, and not with the transparency expected of a state actor, but with the familiar urgency of a government racing to rewrite a story unraveling faster than its propaganda machinery can respond. The allegation appeared almost ceremonially: a dramatic tweet, a recycled photograph, an emotionally charged—but evidence-light—statement. And like clockwork, an ecosystem of aligned propaganda accounts, especially those operating from Afghan and Indian digital clusters, sprang into coordinated action, echoing the claim with remarkable uniformity. Such speed is not organic—it is operational. And when a narrative moves faster than verification, it often signals that verification is precisely what the narrators wish to avoid.

What Kabul presented is an accusation; what the terrain of Khost–Bermal presents is an entirely different reality. For investigators, analysts, and regional security experts, this region is not an empty blank on a map. It is a corridor heavy with insurgent history—a place where the geography itself tells a story of militant transit, factional warfare, and clandestine infrastructure. For nearly two decades, this belt has served as a principal artery for Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Jamaat-ul-Ahrar (JuA), and ISIS-K’s breakaway cells. Satellite surveillance, HUMINT reports, UN Monitoring Team documentation, and repeated ground-based confirmations all narrate the same truth: this corridor is neither a civilian sanctuary nor a typical residential space. It is a cluster of safehouses, bomb-making units, sleeper-cell barracks, weapons transit points, extortion hubs, and cross-border infiltration staging grounds.

Understanding the forensic improbability of Kabul’s claim requires understanding how explosions in this belt have historically occurred. A decade-long catalogue of incidents reveals that a large number of explosions in Bermal, Ghulam Khan, and the Khost outer belt have stemmed from IED mishandling, accidental detonations inside bomb factories, internal turf battles, and targeted assassinations within fragmented militant networks. These blasts exhibit forensic signatures—not the uniform blast radius of aerial munitions. Investigators often observe irregular pressure-wave patterns, asymmetrical structural damage, and residue inconsistent with guided munitions. These are classic hallmarks of explosives stored in enclosed spaces—ammo depots, safehouses, and clandestine workshops—not of precision ordinance delivered from across the border.

This pattern matters. It is not theory; it is empirically evidenced history. When Kabul labels such a location as a “civilian home,” it knowingly strips the context necessary to distinguish a house from a safehouse, a family dwelling from a bomb nursery. In counterterrorism cartography, the difference is not semantic—it is structural. A civilian home does not have blast reinforcement. It does not contain nitrates, pre-assembled detonators, mortar shells, suicide-vest components, or the common tools of violent trade. A militant safehouse often does. When such a stash detonates prematurely, the forensic pattern resembles exactly what Kabul now claims was caused by a Pakistani airstrike.

Complicating Kabul’s narrative further is its timing. This allegation was not made in a vacuum; it arrived on the heels of a series of verified investigations in Pakistan revealing that the attackers in the Islamabad Judicial Complex attempt, the Wana Cadet College assault, and the Peshawar campaign were Afghan nationals who operated from Afghan territory, trained in Afghan sanctuaries, and moved through Afghan channels unhindered. These findings did not merely embarrass Kabul—they cornered it diplomatically. When a state finds itself associated with attacks across its border, it faces difficult questions from neighbors, partners, mediators, and international observers. States under such pressure often resort to diversionary narratives. In political crisis management literature, this is called a preemptive blame deflection strategy: create a parallel crisis—preferably one that portrays your state as the victim rather than the negligent host.

The allegation also follows a noticeable pattern: every time Pakistan prepares a diplomatic or operational response to Afghan-based attacks, Kabul generates a sudden claim of Pakistani aggression. This is not speculation but a recurrent sequence observed across years. When Pakistan struck TTP enclaves in the past, Kabul was silent. When Pakistan signaled any future readiness to respond, Kabul suddenly “discovered” civilian casualties in militant zones. Each time, the alleged strike zones overlapped with TTP routes or ISIS-K transit points. The coincidence is too consistent to be accidental; it is strategic messaging by Kabul aimed at framing Pakistan as the aggressor before Islamabad can expose Afghan soil as the launchpad of attacks.

In investigative analysis, one must also examine the information warfare dynamics surrounding such claims. Within minutes of Kabul’s announcement, old photographs—some from Syria, some from Gaza, and some from previous years in Afghanistan—surfaced on Afghan social media with captions linking them to the alleged Khost incident. Reverse image searches quickly debunked several. Yet they had already fulfilled their purpose: feed the outrage cycle, saturate timelines with emotional imagery, and blur the line between verified facts and recycled archives. In information manipulation studies, this is called the “emotional latency tactic”—release emotionally compelling content faster than investigators can disprove it. The goal is not truth; the goal is virality.

The involvement of Indian propaganda clusters is another forensic indicator of coordination. Indian disinformation networks, particularly those operating through anonymous amplification botnets, have a known history of exploiting Afghan sentiment to shape anti-Pakistan narratives. Their sudden synchronized amplification of Kabul’s claim—without evidence, without verification, and without dissent—mirrors documented patterns observed during previous Afghan-Pakistan tensions. Digital forensics often reveals shared metadata patterns, coordinated posting intervals, and identical message templates. These signatures do not belong to organic users; they belong to networked influence operations.

One must also consider Kabul’s repeated refusal to accept Pakistan’s proposal for joint verification and ground-based investigation teams. This is the clearest forensic red flag. A state confident in its claim welcomes verification because it strengthens its moral and diplomatic standing. A state that refuses verification signals that it fears what verification will expose. Kabul’s refusal is especially striking given that such joint mechanisms exist in several conflict-prone border regions globally. If the alleged target were truly a civilian home, Kabul would have every incentive to allow neutral investigators to confirm it. But if the structure is, as many regional analysts know, part of a TTP or JuA transit chain, verification becomes dangerous—not for Pakistan, but for Kabul’s narrative.

Further complicating Kabul’s posturing is the geopolitical pressure now converging on Afghanistan. Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Iran have all expressed concerns—some publicly, many privately—about Afghanistan’s failure to restrain transnational militant groups. These states, keen to stabilize the region and protect their own emerging economic corridors, have grown weary of Kabul’s assurances that never translate into actions. Under this diplomatic weight, Kabul needs political cover. It needs to portray itself as a besieged state rather than a negligent one. Hence the urgency of crafting an external threat narrative.

The investigative reality, however, is far less dramatic than Kabul’s claims yet far more troubling. The structures in the Khost–Bermal belt are not civilian homes in the traditional sense. They are hybrid dwellings used as logistical nodes, resting points for fighters, small-scale munitions depots, and safehouses for field commanders. The lines between civilian and militant infrastructure in these zones are blurred by design. The Taliban’s own governance model, which depends on tribal-based accommodation, allows militants to operate in spaces where families also reside. This co-location strategy provides militants cover while creating plausible deniability for Kabul. But co-location also means that when a militant safehouse explodes internally—due to faulty explosives, storage mishandling, or internal rivalry—the structure looks superficially like a “civilian home.” Kabul leverages this ambiguity to frame Pakistan.

In forensic conflict analysis, such ambiguity is not unusual; it is weaponized. Groups like ISIS-K, TTP, and JuA often deliberately embed their assets within civilian structures to maximize political backlash after accidental or targeted strikes. Yet Kabul, instead of acknowledging this dangerous practice, exploits it to deny responsibility for hosting militants. When Pakistan points out these hybrid structures, Kabul responds with emotional appeals rather than structural corrections.

The path to resolving these tensions is both simple and difficult: Afghanistan must dismantle militant infrastructure within its borders. It must recognize that allowing TTP and JuA sanctuaries is not merely a security lapse—it is a breach of international responsibility. It must move beyond the political convenience of blaming Pakistan for every explosion triggered by its own negligence. The longer Kabul relies on falsified narratives, the more isolated it becomes diplomatically and the more deeply entrenched its internal fractures grow.

For Pakistan, the direction remains steady. It continues to insist on verification, transparency, and a rules-based approach. It demands only what any state would demand: that its neighbor prevent cross-border attacks launched from its soil. Pakistan has no reason to strike civilians; it has every reason to target terrorists. Kabul’s inability—or unwillingness—to distinguish the two cannot become the basis of regional instability.

The alleged Khost incident is, therefore, not merely a question of one explosion. It is a window into a broader pattern: a state overwhelmed by internal militant entanglements, unable to control its own factions, fearful of international scrutiny, and increasingly dependent on narrative manipulation to mask its security failures. Kabul’s accusation is not evidence of Pakistani aggression; it is evidence of Afghan insecurity. And as long as Kabul continues choosing narrative over responsibility, emotional imagery over forensic truth, and propaganda over partnership, the region will remain hostage to instability.

The world must see this episode not as an isolated claim but as part of a larger pattern—a pattern of evasion, denial, and misdirection by a state unwilling to confront the militants it shelters. Stability in South and Central Asia cannot be built on such foundations. It requires honesty, verification, joint mechanisms, and above all, the political courage to confront uncomfortable truths. Kabul still has an opportunity to choose that path. But its fabricated airstrike allegation suggests it fears the truth more than the instability that denying it will continue to generate.

Egyptian FM to arrive in Pakistan today

Naveed Ahmad Khan

Islamabad:The Foreign Office has announced that Egyptian Foreign Minister Dr. Badr Ahmed Abdel Ati will undertake an official visit to Pakistan from November 29 to 30, following an invitation extended by Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar.

The visit is expected to further strengthen the longstanding and friendly relations between the two brotherly countries.

According to the Foreign Office spokesperson, the two sides will focus on enhancing cooperation across multiple areas, including politics, economy, defense, culture, and people-to-people exchanges. Dr. Abdel Ati and Ishaq Dar will hold both one-on-one discussions and delegation-level talks.

During the meetings, the two countries will review bilateral relations as well as regional and global developments. The latest situation in Gaza will also feature prominently in the discussions, reflecting the shared concerns of Pakistan and Egypt over the humanitarian and security dimensions of the crisis.

The spokesperson noted that the visit will play an important role in deepening the Pakistan–Egypt partnership and opening new avenues for mutually beneficial collaboration. The upcoming engagements underscore the commitment of both nations to further elevate their multifaceted ties.