The rapprochement between North Korea and Russia is widely seen as reducing North Korea’s dependence on China and providing the DPRK with greater strategic independence

The Russia-North Korea rapprochement

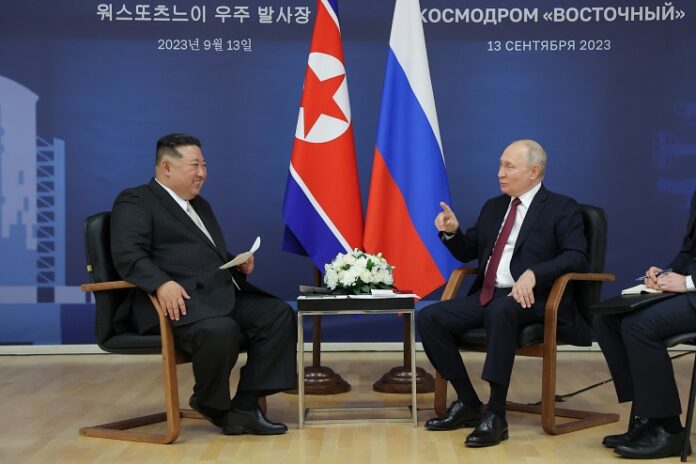

Relations between Pyongyang and Moscow have historically developed countercyclically to relations between Pyongyang and Beijing.[1] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, North Korea became more dependent on China but since the first meeting of their current presidents in June 2023, Russia-North Korea relations have experienced a turnaround, leading to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Pact”, signed in June 2024 which commits both countries to provide military assistance if the other is subjected to armed aggression.[2]

The rapprochement between North Korea and Russia is widely seen as reducing North Korea’s dependence on China and providing the DPRK with greater strategic independence.[3] In official trade data, North Korea-China trade still dwarfs North Korea-Russia trade even though the latter was expected to triple in 2024.[4] However, since September 2023, there has been a steady flow of weapons shipments from North Korea to Russia[5] to make up for ammunition shortages that had emerged during Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine and, by October 2024, North Korea had begun with the deployment of troops to Russian Kursk Oblast. Olena Guseinova of Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul[6] estimated that by October 2024 the weapons deliveries alone had reached a value of between $1.7 billion and $5.5 billion. While this estimate excludes any earnings from North Korean troop deployments in Russia, it already puts trade with Russia at a similar level as official trade with China of about $2.3 billion in 2023.[7]

North Korea appears to have used part of its earnings from trade with Russia to cushion the inflationary impact of a short-terminist policy of increasing wages in the state sector which was rolled out in late 2023.[8] The partnership agreement also includes cooperation in scientific and technological research, in particular in space and peaceful atomic energy, raising fears of Russian support for the DPRK’s nuclear weapons and missile program, directly enhancing North Korean capacity for belligerence. Shortly after concluding the agreement, in November 2023, North Korea finally succeeded – reportedly with the help of Russia – to launch a reconnaissance satellite.[9]

China-North Korea relations

As direct neighbors, the relationship between North Korea and China is ambivalent. North Korea is the only country with which China has a defense treaty – going back to 1961. While North Korea depends on China for an overwhelming share of its trade, the level of trust in the relationship is low: North Korea fears China’s meddling in its affairs and relations have been strained by North Korea’s policy of developing nuclear weapons.

For China, North Korea serves as a buffer against the United States and its allies Japan and South Korea that it perceives as a threat to its own security.[12] Yet North Korea’s belligerence also creates a risk for China of getting drawn into a conflict – a fear which it tried to address when the defense treaty was renewed in 2021: mutual obligations were explicitly limited to cases of aggression instigated by third parties.[13]

China’s approach shifted again in 2018,[16] when the prospect of a US-North Korea settlement emerged, leading to the high-profile – but ultimately unsuccessful – summits between the US President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un in Singapore and Hanoi. Following the announcement of the first Trump-Kim summit on March 8, 2018, Kim Jong-un and Xi Jinping held two meetings, with two additional meetings taking place thereafter.[17]

Subsequent Chinese government visits to North Korea, however, have produced a lack of tangible outcomes. In 2019, tensions surfaced when North Korea appeared to snub China diplomatically. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi was not received by Kim Jong-un, and North Korea sent only a lower ranking government official to the second Belt and Road Forum.[18] Despite this, China, alongside Russia, vetoed UN Security Council resolution 2022/431, which condemned the intercontinental ballistic missile test of March 24, 2022. This marked a strong contrast to the Council’s unanimous condemnation of similar tests in 2017.[19] In May 2025, a joint statement by Russia and China, issued on the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, called to stop unilateral sanctions and military pressure against North Korea. [20]

China-Russia relations

The Ukraine war also brought about a deepening of the relationship – dubbed a “no limit partnership” – between Russia and China, with Russia becoming increasingly dependent on China as a supplier of technology and a market for fossil fuels. Amid growing hostility between China and the United States, the US administration’s recent attempt to improve relations with Russia must have raised some concerns in Beijing.[21] While the Russia – North Korea rapprochement negatively affects Chinese interests in Northeast Asia and Russia has no alternative to the partnership with China in the short term, China’s interests would be ill served if a repetition of the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s happened in the medium term.

China’s response to the Russia-North Korea rapprochement

Amid China’s increasingly adversarial relationship with the United States – dating back to the first Trump presidency – and concerns of losing leverage over North Korea, the prospect of a US-DPRK rapprochement appears to have shifted China’s stance toward its neighbor. While the Russia-North Korea rapprochement is, arguably, less threatening, China still seems to view their relationship with unease.

North Korean belligerence remains a key concern for China. Since 2018, China has tended to shift blame for tensions on the Korean peninsula from North Korea to the United States and its trilateral alliance.[22] But more recently, China’s uneasiness about North Korea has been growing:[23] in October 2024, the Chinese CCTV news channel expressed concern about the complexity of the situation created by the Russia-North Korea alliance, and its impact on the Korean peninsula.[24] Ultimately, however, China has few other options than continue to accommodate North Korea if it wishes to avoid even further destabilization of the situation on the Korean peninsula and there are no signs that it is willing to undermine its own partnership with Russia.

The future, however, looks less promising for North Korea: it remains unclear to what extent the United States is willing to re-engage on the Korean peninsula. While Russia is likely to remain focused on maintaining and rebuilding its military power, an eventual end to its war in Ukraine is likely to shift priorities to its military-industrial complex at home. A China interested in shifting the geopolitical balance in Northeast Asia in its favor might be less interested in an unreliable ally. While it lasts, though, North Korea is unlikely to be the wedge with which to effect change in the balance of power in Northeast Asia. Courtesy of Daily NK Weekly Newsletter